This article is the first in a two-part series. It analyzes two trends in energy management on college and university campuses—technology trends and the decarbonization movement.

Part 2 will examine why schools looking to improve their energy programs might consider partnering with private industry.

As a college or university administrator, do you see yourself as a “Utility Business Executive”? While you may not think of yourself as such, if you have an on-campus energy and utility system, you are indeed a “Utility Business Executive.” Congratulations!

You (and your institution) own and operate an integrated utility business responsible for satisfying your customers’ energy and utility requirements through a mix of procurement, generation, distribution, maintenance, and customer service functions. That’s quite a responsibility—and opportunity.

To be successful in this role, you must follow standard business practices. This includes full-cost accounting, cost recovery, activity-based cost allocation, system renewal and depreciation management, not to mention keeping up with evolving technologies, staff recruitment and training, customer expectations, and operational paradigm shifts.

Historically, while not always easy, running a utility business has as least been straightforward—provide safe, reliable, and affordable services to your customers. In today’s world, however, you are also expected to deliver exceptional environmental performance, resilience to unforeseen events (think COVID-19), expanded choice, and innovation[1]—all while responding to “daunting challenges to long-established business models,”[2] rising costs, and eroding funding sources. Fortunately, there are many emerging trends allowing campuses to productively balance financial realities with risk management and aspirational performance.

Let us start with technology trends. Most campuses have already adopted the “district energy” concept that enables efficiency through economies of scale and load diversification. Utilizing more efficient central resources at a higher utilization rate has resulted in significant energy and capital efficiency relative to disconnected building-level energy resources.

As campus operators seek to move beyond current system efficiencies, though, there are two key technology trends worth noting. The first is a global trend toward lower operating temperatures of district heating systems. Specifically, shifting from steam-based systems to lower-temperature hot water systems. The benefit? The system can reduce units of purchased energy by 50% while still delivering the same amount of usable energy to the buildings. How? Most existing district energy systems consist of a central heating plant with boilers to produce steam. That steam is then distributed through a set of networked pipes to buildings across the campus. Steam systems have inherent losses and inefficiencies. For example, think of visiting a campus with a steam-based system, especially in the northern part of the country, on an early winter day when there is a light layer of snow on the ground. You will likely be able to see exactly where the steam pipes run because the snow has melted above the steam pipes. This is energy loss and it is happening all year long, continuously. In a typical steam system, only one-third to one-half of purchased energy will productively be used in the buildings. In a low-temperature hot water (LTHW) system, supply water is distributed via a similar piping network but at much lower temperatures than steam—temperatures much closer to the surrounding area (e.g., the ground), which reduces the heat loss in the distribution system. This lower temperature also enables the integration of high-efficiency equipment and renewable heating sources, such as heat pumps, heat recovery chillers, solar-thermal arrays, and ground-source heating wells and leads us to our next trend.

The second technology trend is about achieving efficiencies through more advanced, interconnected systems. Historically, each networked series of systems was operated either in heating-only mode or cooling-only mode. This left potential efficiencies on the table while providing less than ideal occupant comfort, as there are many times throughout the year when some spaces need to be heated while others need to be cooled. Replacing isolated heating and cooling systems with a unified “heat-sharing network” presents a tremendous opportunity. The network allows units of energy to be repurposed and recycled among the heating and cooling systems when simultaneous heating and cooling is taking place. This shift can be further enhanced with the use of a ground-source heat exchange system that allows units of energy to be extracted from buildings by the cooling system in the summer, stored in the ground and later reused for heating in the winter.

What’s the catch? Transitioning to a low-temperature hot water “heat-sharing network” may require substantial building conversion costs, disruption to the campus physical environment, and significant modification to campus supply and distribution assets. Campus staff may be resistant since they may not be familiar with the required technologies. Typical five-year capital planning budget cycles are not well-suited to manage the scale and technical complexity of the projects required to complete the transition. However, with proper planning, phasing, and technical and financial engineering, all these barriers can be overcome, allowing campuses to unlock the efficiencies and benefits of the modern district energy system.

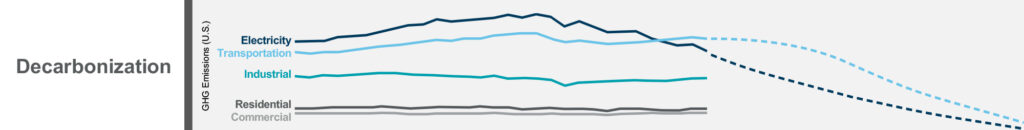

Another macro trend driving this overall transition to newer district energy paradigms is the decarbonization movement. The graph below, based on data from the U.S. Energy Information Administration, shows the history of greenhouse gas emissions by sector in the United States. Note that the electricity sector is the only sector of the economy that has been able to significantly reduce greenhouse gas emissions. These reductions have been enabled by a dramatic decrease in costs of renewable energy technologies over the past decade. This trend is only expected to accelerate as many states and electric utilities have made commitments to completely decarbonize the electricity supply by mid-century. The transportation sector is expected to quickly follow electricity’s decarbonization trajectory as it electrifies with battery electric vehicles.

Like vehicle electrification, the lower-temperature technology trends described above can all be implemented in an all-electric format. Campuses are learning how to shift away from the combustion of fossil fuels toward systems powered by electricity and “recycled” energy.

![]()

Fred Rogers, former vice president and treasurer of Carleton College, calls the shift to lower-temperature, electrically based systems the school’s “bet on electricity[3].”

Capitalizing on these trends can lead to significant operational savings for your campus, a 50%+ reduction in the units of purchased energy, and a 90%+ reduction of on-campus fossil fuel combustion. There are many other co-benefits including an increase in staff motivation and performance, improved thermal comfort, and a clear decarbonization pathway for your campus based on existing, proven technology. These trends provide a once-in-a-generation opportunity for the enterprising campus “Utility Business Executive” who is willing to accept the challenge.

Part 2, “Campus energy transition: Partnership needs and opportunities” is due out in the coming weeks. Check back or subscribe for updates.

This article was originally published on the P3 Resource Center.